From the book Assault from the Sea by Curtis A. Utz

On the morning of 13 September, Rear Admiral John M. Higgins's gunfire

support ships steamed up the narrow channel toward Inchon. At 1010, during

the day's first flood tide, destroyers Mansfield (DD 728) , De

Haven (DD 727), Lyman K Swenson (DD 729), Collett (DD

730), Gurke (DD 783) and Henderson (DD 785), followed by

cruisers Rochester, Toledo, HMS Jamaica and HMS Kenya, entered

the outer harbor. Aware that one disabled ship could block the vital

channel, destroyer officers had their boatswain's mates rig towing gear to

quickly pull a damaged or grounded ship out of the way. Repair parties,

armed with Browning automatic rifles, carbines and submachine guns, stood

by to repel enemy boarders who might attack from nearby sampans or the mud

flats. Overhead, a combat air patrol of Task Force 77 Grumman F9F Panther

jets provided cover.

Rear Admiral

James H. Doyle, Commander Task Force 90; Vice admiral Arthur D. Struble,

Commander Joint task Force 7; and Rear Admiral John M. Higgins, Commander

Task Group 90.6, confer on board Struble's flagship, heavy cruiser,

Rochester (CA 124), on 13 September, 1950

Rear Admiral

James H. Doyle, Commander Task Force 90; Vice admiral Arthur D. Struble,

Commander Joint task Force 7; and Rear Admiral John M. Higgins, Commander

Task Group 90.6, confer on board Struble's flagship, heavy cruiser,

Rochester (CA 124), on 13 September, 1950

At 1145, a lookout on Mansfield cried out, "Mines!"

Commander Oscar B. Lundgren, De Haven's commanding officer and a

mine warfare expert, spied the menacing black shapes of 17 contact mines.

The three leading destroyers fired on the mines with their 20mm and 40mm

guns, plus small arms. A thunderous explosion tore through the air and a

plume of muddy water leapt skyward as one mine exploded. Captain Halle C.

Allen, Commander Destroyer Squadron 9, ordered Henderson to stay behind

and eliminate the remaining mines. Soon afterward, the destroyer sailors

discovered, from the piles of Soviet-made mines they spied ashore, that

the enemy was in the process of completely mining the water approaches to

Inchon.

As the ships moved to their firing positions, propeller-driven Douglas

AD Skyraiders from Philippine Sea blasted Wolmi Do with bombs,

rockets and gunfire. The cruisers remained in the outer harbor, while the

destroyers dropped anchor above and below the island. The destroyers swung

on their anchors on the incoming tide, bows downstream, prepared to exit

quickly, if necessary. The gunners loaded their five-inch guns, trained

them to port and located their assigned targets.

"Ten enemy vessels approaching Inchon," the North Korean

commander radioed in the clear to NKPA headquarters in Pyongyang. He

added, "Many aircraft are bombing Wolmi Do. There is every indication

that the enemy will perform a landing." The Communist officer assured

his superiors that his defense force was prepared for action and would

throw the enemy back into the sea.

In De Haven's gun director, Lieutenant Arthur T. White saw North

Korean soldiers run out and load a gun just north of Red Beach. White

requested permission to open fire and Lundgren gave it. De Haven's fire,

which quickly eliminated the enemy weapon, proved to be the opening salvo

of the prelanding bombardment.

The object of this effort was to stimulate the enemy guns in Inchon and

emplaced on Wolmi Do to return fire so the UN ships could target and

destroy them. For a long eight minutes, the North Koreans failed to rise

to the bait. But then the defenders, men of the 918th Coastal Artillery

Regiment, wheeled out their weapons-mainly Soviet-made 76mm anti-tank

guns-and opened fire, hitting Collett seven times, Gurke three.

The response was devastating. The gunfire support ships poured 998

five-inch rounds into the island and defenses in front of the city. At

1347, with many enemy guns silenced, Allen signaled the retirement order

to his destroyers, which headed for the open sea. The cruisers provided

covering fire for this movement and then brought up the rear of the

column.

North

Korean guns emplaced ashore returned the fire of the Allied surface ships,

sometimes with telling effect. Sailors pose with a hole blown in the

destroyer Collett (DD 730) by a Communist 76mm gun

North

Korean guns emplaced ashore returned the fire of the Allied surface ships,

sometimes with telling effect. Sailors pose with a hole blown in the

destroyer Collett (DD 730) by a Communist 76mm gun

Before the ships could clear the harbor, however, one of the few

remaining Communist guns exacted revenge on Lyman K Swenson. Two

North Korean shells exploded just off the destroyer's port side, killing

Lieutenant (jg) David H. Swenson, ironically the nephew of the sailor for

whom the ship was named. Enemy fire wounded another eight men in the

bombardment force that day.

That night Higgins and Allen conferred with Struble in Rochester. Although

pleased with the day's action, Struble ordered the ships and aircraft to

give Wolmi Do "a real working-over" the following day. The mine

threat remained because gunfire had eliminated only three of the devices

and the task force minesweepers were several hundred miles away from

Inchon. Because of the lack of small combatants, the minesweepers had been

assigned to troop transport escort duty. Struble now ordered the ships to

make best speed to the operational area, even though they would not arrive

until 15 September. Soon after midnight the admiral dismissed his officers

so they could grab a few hours of sleep and prepare for the next day's

combat.

Sailors

prepare to commit the body of Lietenant (jg) David Swenson to the deep on

the morning of September 14.

Sailors

prepare to commit the body of Lietenant (jg) David Swenson to the deep on

the morning of September 14.

The following morning, the ships of the bombardment group hove to, with

colors at half-mast and crews at quarters. A boatswain's mate in Toledo piped "All hands to bury the dead." After a simple service,

a Marine rifle salute and the playing of "Taps", bluejackets

committed Lieutenant (jg) Swenson's remains to the deep. Somber but

determined after this ceremony, the men of the cruiser-destroyer group

again prepared for action. Note

The ships once again moved up Flying Fish Channel. As the force closed

Inchon, Toledo fired on one mine, exploding it. The damaged Collett dropped off and destroyed another five of the deadly "weapons

that wait."

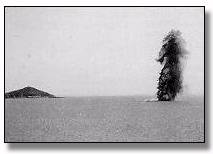

Naval

gunfire from heavy cruiser Toledo (CA 133) explodes a Soviet-made sea mine

in the approaches to Inchon on September 14. If the enemy had had more

time to lay mines off Inchon, the result might have been disastrous to the

operation

Naval

gunfire from heavy cruiser Toledo (CA 133) explodes a Soviet-made sea mine

in the approaches to Inchon on September 14. If the enemy had had more

time to lay mines off Inchon, the result might have been disastrous to the

operation

At 1116, when they came in range of targets ashore, the cruisers loosed

a salvo. NKPA gunners then opened up on HMS Kenya, the closest

cruiser to shore. Captain Patrick W. Brock, RN, Kenya's skipper,

felt that "the enemy gunners were either very brave or very

stupid," because even before the cruiser could return fire, attack

aircraft obliterated the offending guns. In the next 75 minutes, the

destroyers hurled over 1,700 five-inch shells into Wolmi Do. The cruisers

reentered the fray and as Marine and British Fleet Air Arm pilots spotted

targets, they blasted positions near Inchon and on Wolmi Do. One Valley

Forge pilot observed that "the whole island," referring to

the once-wooded Wolmi Do, "looked like it had been shaved."

The

after turret on Toledo (CA 133) fires a salvo of eight-inch rounds at

targets near Inchon during the preinvasion bombardment.

The

after turret on Toledo (CA 133) fires a salvo of eight-inch rounds at

targets near Inchon during the preinvasion bombardment.

The Advance Attack Group, then in the Yellow Sea, stood in toward

Flying Fish Channel. Near dusk and sixty-five miles from the objective,

Commander Clarence T. Doss, Jr., in charge of three rocket bombardment

ships (LSMRs), spied a huge pillar of smoke on the horizon to the east.

Doss knew this meant that UN ships and planes were plastering the enemy

defenders. He passed that "welcome news" to all hands.

[ Up ] [ Six Brave Ships ] [ Eddie Snelling's Inchon Invasion Photos ] [ Gunnery Officer's View ] [ Bob Sauer Remembers ] [ 10 Enemy Vessels Approaching ] [ Enemy Vessels Approaching ] [ Land The Landing Force ] [ Assault on Red Beach ] [ Operation Chromite ] [ Shoot Us If You Can ] [ The Taking of Wolmi-do ]