|

Click on map for larger image |

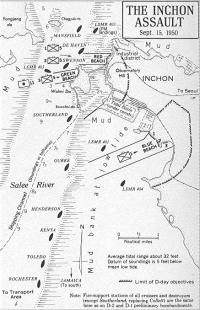

At seven in the morning the cruisers and destroyers entered Flying Fish Channel. The day was D-2, September 13. Before dawn, wearing the flag of Admiral Struble, Rochester had joined the darkened, radio-silent column and formed on Toledo, flagship of Rear Admiral John M. Higgins's Gunfire Support Group. Astern of Rochester were HMS Jamaica and Kenya, British light cruisers. Ahead were five destroyers: Mansfield, DeHaven, Lyman K. Swenson, Collett, and Henderson. A sixth destroyer, Gurke, broke across the dark western horizon and cut into the formation; amid a flurry of blinker signals she closed Toledo's starboard quarter, expertly sent over a heaving line, and transferred a canvas pouch. This was "the late dope": last-minute target information, yesterday's aerial photos, and the latest intelligence, obtained only two hours earlier from Valley Forge, flagship of the fast carriers. Then the bombardment group turned east toward Flying Fish Channel as the sun, red and round, broke through the gray haze of mist and woodsmoke from cooking fires ashore. The tide was still ebbing as the leading destroyers poked into the channel. At full low as they passed Palmi Do, it would be flooding when they reached bombardment stations at Inchon. Here was another of the infinite expert calculations required to make the operation succeed: with scant turning room up-channel, the rising tide would keep the anchored destroyers stemming it, bows downstream and full broadsides uncovered toward the enemy throughout the shoot. When the moment came to retire, even to slip anchor if need be, they would be headed out.

Overhead, covering the advance, were the Panther jets of Task Force 77's combat air patrol, or "CAP." In addition, a strike group of heavily armed ADs had reported in to Admiral Higgins at 0700. Aboard the destroyers final preparations were in -progress: additional boilers being lit off and put on the line for full power on short notice; fenders and towing gear being rigged out in case a cripple needed help; repair parties being armed, not with cutlasses but with rifles (the world's most ludicrous sight: a sailor with a rifle), so as to repel boarders or suicide sampans; then an early steak dinner for all hands before the covering air strike and the clangor of General Quarters.

Now the time was at hand to see whether Admiral Doyle and General Smith had been right in their insistence on a methodical naval gunfire bombardment. Would the destroyers goad the gunners of the 918th Coast Artillery into disclosing themselves?

Meanwhile, there was another disclosure. At 1145, as Mansfield, first in column, approached Pukchangjaso, an islet below Palmi Do, the port bridge-wing lookout sang out, "Mines!" Moments later the same report came from DeHaven, next in column. Riding on the muddy surface, exposed by extreme low tide, were the ugly black casings of 17 Russian contact mines.

Momentarily, perhaps because it was so ominous, the sight was unbelievable; DeHaven's skipper, Commander O. B. Lundgren, a minewarfare expert, had no doubts and quickly confirmed Mansfield's tentative report. The three leading ships opened fire with rifles and 40mm and 20mm guns, seconds later there was a thudding explosion and geyser of mud-"After that, nobody doubted me any further," recollected Lundgren.

Here was a turn of events, conceivably the very worst turn of events, for which preparation had not been made. The few minesweepers in the Far East had been pressed into service as escorts, and were far behind with the transports rather than ahead of the destroyers in the Salee River. For the four cruisers, there was no problem: their bombardment stations -at very long range for such work-were down-channel just below the mines. For the destroyers it was another matter; if more mines lay in the channel higher up, they would soon find out. Meanwhile, Captain Halle C. Allen, USN, the destroyer squadron commander, detached his rear ship; Henderson, with orders to destroy the mines by gunfire, and pressed on in the brilliant morning sunshine toward Wolmi Do.

Fortunately the channel was clear. Douglas MacArthur's luck had held. What had happened was that, after the British had shelled Wolmi Do on September 5 and 6, using the area now mined, the North Koreans had planted two fields of contact mines in case the Royal Navy came back. These fields were also located so as to commence closure of the junction of Flying Fish and East Channels. Later, when the harness cables arrived for the more dangerous ground mines, general mining would proceed at Inchon, and the cork could be put into the bottleneck between Pukchangjaso and Palmi Do.

As the cruisers' anchors clattered down from the hawseholes and the destroyers moved up, the ADs from the fast carriers shrieked down on Wolmi Do. At headquarters in Inchon the defense commander reached for a message blank and his ink block. Quickly brushing in the characters, he wrote :

Ten enemy vessels approaching Inchon. Many aircraft bombing Wolmi Do. Every indication enemy will carry out a landing. All units my command are directed to be ready for battle; all units will be stationed in their assigned positions so they may throw back enemy forces when they attempt their landing operation.

The report was a good one. Alas for the Communists, there is no evidence that higher headquarters accepted it. In any case, even if the harness cables had arrived that very afternoon, time had run out.

At 1242, Gurke's anchor went down. Six minutes later, three miles upstream, north of Wolmi Do and Inchon, Mansfield anchored at the other end of the line. It might have been—in a very real sense it was—a visit by the Fleet. Aboard sampans in the harbor and the channel, white-robed Koreans in black hats stared at the warships as the 5-inch mounts and directors trained out to port. Even though Philippine Sea's AD Skyraiders slugged and swooped at Wolmi Do, a Los Angeles Times correspondent, observing from the bridge of Rochester, said the island "looked like a picnickers' paradise, green-wooded and serene."

A signal-"Commence scheduled mission"-fluttered at the dip from Mansfield's starboard yardarm. In 12 minutes Commodore Allen would two-block his signal just as the last AD pulled out of her dive. Then the destroyers would open fire. At the root of the Wolmi Do causeway, beside a railroad siding, Commander Lundgren could see a pyramid of black cylinders-Russian contact mines. That was how close it had been.

From DeHaven's director, Lieutenant Arthur T. White, USN, the gunnery officer, could see something else. On the tongue of land north of Red Beach in Inchon proper, a gun was being run out and uncovered. "Captain!" he reported over the battle phones. "They're running out a gun .... Captain! They're loading the gun . . . . Captain! Request permission to open fire."

"Permission granted," came the word, and seven minutes early, before the anchor windlass detail could clear the forecastle, DeHaven's 5-inch guns began the battle. The forward mount's blast nearly blew the chief boatswain's mate overboard while he was stopping down the starboard anchor. It also disconcerted Commodore Allen, a man who went by the book and kept a weather eye on how things might look to higher authority. But Lundgren had a good excuse, or so Admiral Struble thought when he heard the story, and there the matter rested.

Just as DeHaven ceased fire (target destroyed), the other four ships opened. Firing deliberately, from ranges as close as 1,300 yards, under the muzzles of masked enemy guns, the destroyers commenced to probe.

For just eight minutes the Communist gunners held fire. Then they took the bait. A 76mm gun barked and flashed from a cave on the slope of Wolmi Do. Seconds later a high-velocity antitank shell hulled Collett.

"A necklace of gun-flashes sparkled around the waist of the island," reported the Associated Press man (Relman Morin) aboard Rochester. "The flashes were reddish gold and they came so fast that soon the entire slope was sparkling with pinpoints of fire."

Within the next few minutes intense automatic-weapons and mortar fire were directed at the ships above Wolmi Do (Mansfield and DeHaven) while Swenson, Collett and Gurke (off Wolmi Do or immediately downstream) came under hot fire from the 76mm guns on Wolmi and heavier weapons on Observatory Hill in Inchon.

Collett took the punishment. Five hits by armor-piercing shell, at close range, smashed into her hull. The wardroom was hit (this, a dud, came to rest on the transom), fuel lines were cut, the plotting room damaged and the main-battery computer put out of action, guns had to go into local control, and old-style pointer fire, telescope cross-hairs on the targets, kept the ship fighting. Three minutes after Collett took her first hit, Swenson, next upstream, came first under mortar and heavy small-arms fire, then from the 918th Coast Artillery's heavily revetted 76mm guns on Wolmi Do's northwest face. Gurke, below Collett, was straddled by an enemy salvo at 1330, then by another and another. At 1346, within the space of two minutes, three shells hit home: a 40mm gun was knocked out, a torpedo tube jammed, a stack punctured-all superficial to the ship's fighting power.

As the enemy showed his hand, the destroyers hit back. Between 1253, when DeHaven opened fire, and 1347, when Commodore Allen signaled retirement, they fired 998 rounds of 5-inch onto Wolmi Do and parts of Inchon. Now, with the hornet's nest buzzing, it was time to head downchannel, and in reverse order, under full power, the "sitting ducks" swept through the shell splashes, dueling the enemy with after mounts as forward guns ceased to bear. DeHaven and Mansfield, which had been above the coast artillery arcs of fire, ran the batteries at 25 knots, swamping small craft and sampans with their bow waves and nearly broaching Henderson as they raced by, fantails low, guns still blazing and black smoke pouring from stacks.

Although Swenson's bridge had rung up turns for 31 knots, 23 was all she could get in the muddy shallows. With Blue Beach two miles abeam at 1402, she came under fire—a departing salute—from the battery on Observatory Hill. A two-gun salvo hit close aboard, 25 yards to port. On the ship's 40mm director, a junior lieutenant two years out of Annapolis was ripped by fragments and fell dead. His name was David H. Swenson. He was the nephew of Captain Lyman K. Swenson, USN, killed in the South Pacific, the destroyer's namesake. note

The salvo that killed Lieutenant Swenson was the enemy's final blow. Now the reconnaissance mission was accomplished—"Successfully, the Navy will say," wrote a correspondent. "Gloriously is a better word."

Below Palmi Do the cruisers opened up with 8-inch and 6-inch guns to cover the destroyers' withdrawal. As they were anywhere from seven to ten miles from Inchon and Wolmi Do, and air-spotting arrangements had been badly muddled, the heavy ships' counterbattery fire, while loud and rapid, was far from precise or accurate. Then the planes from the fast carriers raked Wolmi Do again and the destroyers' dead (1 only, Lieutenant Swenson) and wounded (8) were transferred by whaleboat to Toledo, whose sick bay could best handle them. As the planes headed out to sea, the cruisers fired for another half hour and stood down Flying Fish Channel for the night.

Off the channel entrance with deep water and sea room, the fire support group took night dispositions and prepared to darken ship. In the twilight, while there was still light to come alongside, Admiral Higgins's barge and Commodore Allen's gig closed Rochester for conference with Admiral Struble.

Two matters dominated the discussion. Point 1-the 918th Coast Artillery had amply justified the apprehensions of Admiral Doyle and General Smith. Obviously Inchon was defended—Wolmi Do most evidently so—and those defenses were far from neutralized. A full day's work ("a real working-over," said Struble's report) would be required tomorrow for the destroyers, cruisers and Task Force 77's aircraft. And on that last subject, air spotting had better improve—communications between planes and ships had been terrible, and the pilots (theoretically supposed to have basic qualifications as gunfire spotters) were wholly unfamiliar with the process.

Point 2—mines—nagged at everyone who had seen those shapes between Pukchangjaso and Palmi Do, let alone those who, like Commander Lundgren, had actually observed piled mines ashore. Admiral Struble could well remember a conversation in Tokyo when MacArthur had said, "You're confident, aren't you?" and he had replied, "Yes the worst hazard, except for large Russian air intervention, would be mines." Now nothing could be done, mines or no, but to send an urgent dispatch telling the minesweepers to abandon their charges and hasten forward. Just before midnight the meeting broke up. By the time Higgins and Allen were back on their flagships, it was D-1.

In the morning, again screened with planes from the carriers (and this time with a fleet salvage tug in company), the cruisers and destroyers stood in toward Inchon. Out in the channel mouth, at eight bells, the formation hove to, colors at half-mast, Marine guards paraded on the cruisers, crew at quarters in all ships, while in Toledo the boatswain's mate piped the word, "All hands to bury the dead." After the padre's simple, immemorial sentences of committal, the volleys from the Marines and the poignant strains of "Taps," Lieutenant Swenson, in a sailor's shroud of canvas, was given to the deep. Ten minutes later column was formed and the force was steaming toward the enemy.

At 1116, as the destroyers picked their way up the Salee River, the cruisers opened fire. This time the spotters were on station and their radios worked. Even so—the In Min Gun still had plenty of fight—a shore battery promptly took on HMS Kenya, the inshore cruiser, prompting Captain Brock, her CO, to remark, "The enemy gunners were either very brave or very stupid . . . ." In either case they paid for their bravery (or stupidity) by a heavy air strike as the destroyers closed in. One Valley Forge pilot reported that there was no more vegetation left on Wolmi Do: "The whole island looked like it had been shaved."

There were no niceties today about destroyers opening fire. Again DeHaven opened the ball: at 1242 she took on one of the cave-mounted 76mm guns on Wolmi Do's southwest face. Four minutes later, Swenson's 5-inch mounts went to work against a target from yesterday—a gun emplacement on the west tip of the island. Reflecting her lack of familiarity with the target areas, Henderson, which had replaced Collett, waited until 1305 to be sure she had a target, and then joined in. For 75 minutes the destroyers hammered away, and it was 40 minutes before they drew a feeble reply. As they withdrew, the shore batteries remained silent; the five destroyers had fired 1,732 rounds at Wolmi Do—barely less than the number of 5-inch shells that hit Omaha Beach before the Normandy landings.

Overhead, the air spotters (Marine pilots who knew how to shoot) brought in the cruisers' guns for a useful hour's work on military targets now disclosed in Inchon (Admiral Struble had underscored that he wanted no indiscriminate bombardment of the crowded town) and on battered Wolmi Do. Then, covering the fire-support ships' retirement, the airplanes went to work again. The final report, from one of the Marine pilots of VMF-323, said Wolmi Do was "one worthless piece of real estate." So the island looked from the air. How would it look to the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines?

| Copyright © 1997-2023 USS DeHaven Sailors Association 2606 Jefferson Avenue, Joplin MO 64804 Contact Us |