The Assault on Red Beach

From Victory at High Tide by Robert Debs Heinl, Jr. Colonel,

USMC (Ret)

Get

the book

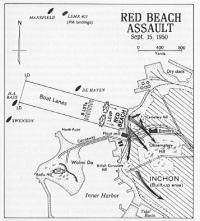

While the victors of Wolmi Do spent a warm and pleasant afternoon watching Inchon, the preliminaries were going ahead for the main assault.

At midday the transports and LSTs for Red Beach came up to Wolmi Do. At long last, steaming four bells and a jingle, the minesweepers arrived and were combing the approach channels. (In addition, there was another mine scare: frogmen in the water around Wolmi Do reported mines on Red Beach; DeHaven's Lundgren, a former mine specialist, observed carefully through powerful glasses, worked over the area with 40mm fire, and reassuringly reported that it was nothing but fish stakes.)

To keep Inchon sealed off, Admiral Ewen kept flights of Task Force 77 ADs hitting targets and interdicting hostile movement within a 25-mile radius of the landing area. He could be generous with aircraft this important day because he was about to receive a third fast carrier, USS Boxer, which, despite a broken reduction gear, was approaching Task Force 77 on three shafts at 26 knots. Boxer had made three transpacific runs since mid-July, ferrying 161 badly needed Air Force airplanes on her first trip west (besides nailing up a Pacific blue ribbon that still stands, for an eight-day crossing from San Francisco to Tokyo) ; then flashed back to embark an Atlantic Fleet air group ferried in from Norfolk, and returned to Korea. Past due for overhaul when the war began, battered by Kezia and limping though she was, Boxer joined up proud as Oregon at Santiago and launched planes on schedule.

Inshore of the fast carriers, the jeep carriers Sicily and Badoeng Strait were carrying out a flight schedule that taxed every resource. Limited by pilot rather than plane availability, the schedules worked out by Lieutenant Colonels James L. Neefus and Norman J. Anderson, the two senior Marines afloat, called for at least two missions per pilot and, in many cases, three. Anderson, a short, alert twinkly-eyed pilot, was, as tactical air coordinator, aerial ringmaster of all close support for the ground Marines. This day and the next, he flew five sorties, totaling 16 hours in the air.

|

At 1430 the tempo of bombardment picked up. The scheduled pre-H-hour fires commenced. Toledo and Rochester, again relying on Marine air spotters, began to drop 260-pound 8-inch shells into the eastern part of Inchon and the northeastern outskirts. Jamaica and Kenya, today using Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm spotters from Triumph, whose spotting procedure (not to mention their English) was more intelligible, covered areas around Blue Beach with their 6-inch guns. DeHaven and Swenson -which could support the assault battalions of the 5th Marines on Red -methodically worked over the beach area (railroad yards, brewery, gas tanks, factories, godowns) with 5-inch. As the naval gunfire intensified, fires began to break out in the lower town, adding their smoke to the dull overcast.

Fifteen minutes after the fire-support ships resumed work, Admiral Doyle two-blocked the expected signal from Mount McKinley: "Land the Landing Force." Soon afterward, he signaled that H-hour (the hour the first waves were to hit Red and Blue Beaches) would be 1730.

Now heavy-laden ADs and Corsairs from Ewen's fast carriers concentrated on Red Beach with 500- and 1,000-pound bombs, 5-inch rockets, and strafing. More fires broke out. The butane tanks north of the beach flared with fierce white flame and black smoke. A nearby factory flamed up. Watching from Mount McKinley's bridge, Captain Martin J. Sexton, General Smith's aide, saw an unforgettable panorama. "The whole area for miles," he remembered, "was obscured by smoke and debris and burning fires."

|

| Map of the assault click for larger image |

Aboard attack transports Henrico and Cavalier, the assault battalions of Lieutenant Colonel Raymond L. Murray's 5th Marines were boating. It may seem strange that a regiment assigned the main effort-and that into the bowels of an Oriental city on a dark night-should be commanded by a lieutenant colonel. But Murray, burly, forceful and tenacious, had fought the 5th Regiment with distinction all through the perimeter, and General Smith would not have traded him for most colonels.

If there could be any such single unit, Murray's regiment was traditionally thought of as the elite of the Corps. Aside from the compelling military factors of seasoning and recent victorious battle experience, it seemed altogether appropriate for the 5th Marines to be in the forefront of the battle. Its colors heavy with battle streamers from France, from Nicaragua, from Guadalcanal, New Britain, Peleliu and Okinawa, and with unit honors ranging from the French Fourragère to our own Presidential Unit Citation, the 5th Regiment held a special position in the mystique of the Corps.

In the forefront of the 5th Marines, its 1st and 2d Battalions (under Lieutenant Colonels George S. Newton and Harold S. Roise, respectively) were to land abreast-each in deep, narrow column of companies across the left and right portions of Red Beach. The latest aerial photographs of this narrow, 650-foot quay, with its stone seawall, showed only too clearly a cluster of bunkers and trenches on the left, while the whole beach was dotted with emplacements, more bunkers, and connecting trenches. In the words of Captain Frank I. Fenton, one of Newton's company commanders:"

It really looked dangerous .... There was a finger pier and causeway that extended out from Red Beach which reminded us of Tarawa, and, if machine guns were on the finger pier and causeway, we were going to have a tough time making that last 200 yards to the beach.

At 1704, with rain squalls beginning to pelt the landing craft, the LCVPs carrying the assault platoons of the leading companies (A from the 1st Battalion, E from the 2d) were at the line of departure a mile offshore. Even from this distance, amid smoke and haze, the initial objectives stood out clearly: Cemetery Hill (foreign burial ground of old Chemulpo), key to Red Beach, a sheer reddish cliff to seaward but sloping down to the right; Observatory Hill, the observatory tower sharply defined, a lunette-shaped redoubt commanding the inner harbor and city; and, to the right and lower, British Consulate hill, overlooking the harbor master's deserted, riddled headquarters. Newton's battalion must seize Cemetery Hill, then the northern horn of the Observatory Hill lunette; Roise and the 2d Battalion were to take British Consulate hill, then the southern horn of Observatory Hill. In regimental reserve, Taplett on Wolmi Do would bring his 3d Battalion across the causeway and support the attack as needed

Observing intently from Mount McKinley-he had commanded a platoon of the 5th Marines in France-General Shepherd caught the scene for his journal:

We watched the troops disembarking in small boats from the transports around us and their movement to the Line of Departure. It was overcast and smoke from the burning city made it difficult to observe the final run for the beach. As H-hour approached, the crescendo of fire increased.

Toledo now began dropping 8-inch shells on Observatory Hill while Rochester interdicted the outskirts and approaches to the town: no reserve units must be allowed to enter, no artillery batteries to occupy positions from which to shell the beaches. Mansfield began raking Red Beach with airbursts. DeHaven's 5-inch guns shelled the north face of Observatory Hill while Swenson worked on Cemetery Hill and the jumble of gas tanks, chimneys and railroad yards to the left. Hard by Mansfield up-channel, LSMR-403 roared, hissed and shook as she began to loose off 5-inch rockets (a hundred a minute for the next 20 minutes) at the beach and north flank.

The red and white 1-flag was at the dip on H. A. Bass from which each boat wave would be dispatched; now it went up. Two minutes later, at 1724, the flag went down and the first wave-eight LCVPs, carrying four platoons of Marines-gunned across the line of departure toward the beach.

As the landing craft forged in, Taplett's mortars, machine guns and tanks opened up from Wolmi Do on the right. Able to observe their own tracers and fall of shot, as well as the advancing waves, gunners on Wolmi Do could fire on Red Beach until the last instant without endangering the assault troops. By way of a bonus to this planned fire support, enterprising Marines of the 1st Tank Battalion turned an undamaged Russian 76mm gun on its former owners and pronounced it a good-shooting weapon.

When the leading LCVPs were midway to the beach, the naval guns fell silent. For the next five minutes VMF-214 and 323 had their turn. Led by the two squadron commanders (Lieutenant Colonel Walter E. Lischeid and Major Lund), the Corsairs gave the beach its final treatment. Like Major Floeck who had attacked Wolmi Do in the morning, Lischeid was an aviator whose days were numbered: within ten days, again supporting the 5th Marines (and flying a Corsair numbered 17, the same unlucky number as Floeck's) Colonel Lischeid was destined to crash flaming into the outskirts of Seoul.

Besides the Corsairs, Navy ADs joined in. First Lieutenant James W. Smith, forward air controller with the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, spotted a target as his LCVP neared the beach, called in a strike and had it under attack by Skyraiders before the leading wave was ashore. The support was so close that the boats were pelted with spent 20mm empties as the ADs roared past.

The wind was blowing directly along the beach so that the heavy smoke from fires ashore provided a screen as effective as if it had been put down by ships' guns and aircraft. On the point to the left a large fire was sending up dense black smoke. Behind, beyond the dry-dock, a huge, bright, hot fire shone through. All along Red Beach, amid the drifting smoke were angry red pinpoints of spreading flame. To the Herald-Tribune's Marguerite Higgins, landing with the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, Wolmi Do "looked as if a giant forest fire had just swept over it…."

Beyond was Red Beach [she continued]. As we strained to see it more clearly, a rocket hit a round oil tower and big, ugly smoke rings billowed up. The dockside buildings were brilliant with flames. Through the haze it looked as if the whole city was burning .... The strange sunset, combined with the crimson haze of the flaming docks, was so spectacular that a movie audience would have considered it overdone.

Observatory Hill, hammered by the 8-inch shells and the strafing, was masked in a solid black cloud rising high above the town. Against this backdrop of havoc, Cemetery Hill stood in clear relief.

So did the Red Beach seawall, which Time's James Bell said "seemed as high as the RCA Building." The LCVPs (some painted Truman's Police Force, for the famous letter had not gone unnoticed) drew near. In the boats, gunnery sergeants rasped, "Lock and load. Runners out first. Keep your goddamned heads down." As they saw the stone wall ahead, officers and NCOs looked for breaches while others readied scaling ladders-mostly homemade by the 1st Engineer Battalion-or (in later waves) stood by furled cargo nets with steel pickets and sledges to anchor them atop the wall. Underfoot, each boat had two long planks so that Marines could get across mud flats in case of grounding.

Coxswains jockeyed for final positions-there were no soft spots on this ironbound beach. Then, as the boats crunched against the seawall and hung in place with engines, leaders sprang up the rickety, bobbing ladders, over the top like a trench assault on the Somme, and the riflemen followed them into the smoke. Flying low and slow over the beach in his blue Corsair, Norm Anderson flashed word back to Mount McKinley: "Scaling ladders are in place and Marines are over the wall."

The time was 1733 when Company A, 5th Marines, hit Red Beach. At the seawall was a trench, on the left a bunker spitting burp-gun slugs, and from back in the smoke, farther left, heavy rifle and machine-gun fire. To the front, across 200 yards of flat, only 130 feet high but looking like a miniature Suribachi, rose Cemetery Hill. This was the objective of Technical Sergeant O. F. McMullen's 1st Platoon, one of whose boats (McMullen's own) had conked out offshore and, with the half-platoon cursing to no avail, was drifting gently in with the tide. The other half platoon, led by Sergeant Charles D. Allen, got over the seawall only to be pinned to the deck, with casualties, by heavy fire from the bunker.

On Allen's right, Second Lieutenant Francis W. Muetzel found a breach and led the 2d Platoon through it. Stopping to toss grenades into a pillbox whose silent machine gun stared at them coldly, the leading fire teams advanced smartly around the right of the hill, for Muetzel had no mind to be stalled against the face of the cliff. While the support collared six groggy prisoners from the pillbox, Muetzel headed across the railroad yards, veered right and made for his objective, the Asahi Brewery. This compelling objective was high in the minds of A Company because Colonel Newton had promised the 1st Battalion a heroic beer bout if the brewery and contents were taken intact.

While Muetzel advanced on his brewery, things went from bad to worse on the left. First Lieutenant Baldomero Lopez (a World War II Navy veteran who graduated into the Corps via Annapolis) landed the 3d Platoon amid the 1st. Hurling in a grenade, he took out the bunker to the front, then pulled the pin and drew back to throw a second into another bunker. A burst of fire caught him, right arm and shoulder, and he toppled. The grenade's striker flicked up, the primer popped, sputtered and smoked beyond reach of his wounded arm. "Grenade!" he cried (the last word he spoke) ; then, lurching toward the deadly thing, got it crooked in his elbow, cradled it into his body and so died.

All these events took place during the first five minutes of the landing. Then, exactly at H+5, Captain John R. Stevens (who had commanded Able Company unscathed all through the perimeter) landed through the same breach as Muetzel. Receiving word of Lopez's death, he turned to his exec, First Lieutenant Fred F. Eubanks, Jr., and said, "Lope is dead -take over there and get them organized and moving."

When Muetzel reported that the brewery was his, Stevens ordered him back to the beach. Without Cemetery Hill there would be no landings over Red Beach.

As Muetzel led his people back again, he got a better look at the hill. Its south and rear (east) faces sloped easily up. Quickly the twenty-four-year-old lieutenant changed direction, re-formed for attack, and moved onto the hill. Taking a surprised cluster of infantry prisoners as they advanced, the Marines drove into the emplacements of the 226th Regiment's mortar company, bagged the surviving members of the company, and herded them downhill under guard. From the crest, now theirs uncontested, they could see a grenade duel around an enemy bunker on the north flank. Just as Muetzel was issuing breathless orders to wade in, he saw a long burst of flame envelop the bunker, and the Marines below clambered to their feet and advanced. Cemetery Hill was taken, the beach was clear and Red was open. But there were eight dead Marines on the flat, and the Navy corpsmen had 28 wounded from A Company to transfuse, ligate, splint, patch, tag and evacuate.

To the right, the first wave of Captain Samuel Jaskilka's Easy Company, landing at 1731, beat Able Company onto the beach by two minutes and thus could claim to be the first Marines in town. Lieutenant Edwin A. Deptula, a Basic School classmate of Muetzel's, got his platoon up and over the wall, covered the landing of the rest of the company and then, with little opposition, headed down the railroad tracks to the right, past a five-story factory with every window aflame, toward British Consulate hill. At 1845, still almost unopposed, Company E held this objective and the lower face of Observatory Hill to the left. Rearward, Colonel Roise had the rest of the 2d Battalion ashore in position around the Nippon (now the Dae Han) Flour Mill at the base of Wolmi Do causeway. The 5th Regiment's right was secure, and the 2d Battalion could now prepare to take its share of Observatory Hill.

Because infrequently exposed-at least on the receiving end-American troops, even Marines, sometimes underestimate the deadliness of naval gunfire. Soon after 1800, as the eight LSTs approached Red Beach at flood tide, men of the 5th Marines had a vivid opportunity to correct misapprehensions on this score.

Among many daring features of the Inchon plan the landing of eight LSTs on a rigid schedule of time and tide within 60 minutes after H-hour was one of the boldest. Audacious in any circumstance, this maneuver was trebly so for the rust-eaten ships and novice officers and men to whom the job fell. The LSTs were mostly repossessed from Japanese island trade, stinking, said the captain of LST-799, "with a penetrating odor of fishheads and urine." Only one LST skipper had previous experience: he had actually beached his ship twice before D-day; crews and officers were mainly mobilized reservists.

|

| Landing craft at Red Beach-click for larger image |

Soon after six in deepening twilight the boxlike, single-screwed arks waddled in column toward Red Beach. Large, slow, conspicuous, they presented admirable targets for everything the NKPA could still shoot. In a shower of mortar and machine-gun fire, LST-859 led the way into a beach far from secure. Gun flashes--theirs? ours? whose?-still sparkled atop Cemetery Hill and on the left half of the beach. Following the 859 at five-minute interval, LST-975 and 857, loaded, among other combustibles, with gasoline, ammunition and napalm, took mortar hits. Ammunition trucks on the 914 were hit and caught fire, but sailors and Marines knocked down the flames with fog and CO2. Eight drums of gasoline on the 857 were punctured in one machine-gun burst. Small-arms fire ricocheted, pinged and clanked on bow doors, ramps and superstructures.

Nobody can really blame the sailors for firing back but their choice of targets was not very discriminating. Shooting up all Red Beach in a fireworks display of un-aimed, high-intensity, short-range fire from 3-inch, 40mm and 20mm guns, seven LSTs (the eighth, 914, held fire) briefly made Inchon harbor unsafe for friend or foe. The 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, crouching for dear life in the lee of the Nippon Flour Mill, took more casualties that day from the LSTs' guns-one dead, 23 wounded-than it sustained from the enemy. Lieutenant Muetzel and his platoon were blasted off the crest of Cemetery Hill toward the enemy, whose machine-gun fire from Observatory Hill they found preferable to the hail of naval gunfire.

By 1900, when all LSTs had beached, Marines, braving the friendly guns, managed to stem the torrent, and peace returned to Red Beach."

| Copyright © 1997-2023 USS DeHaven Sailors Association 2606 Jefferson Avenue, Joplin MO 64804 Contact Us |