Shootout in Tokyo Bay

The order to be prepared to scuttle their ships seemed a bizarre mandate to the men of DesRon 61 when victory in the Pacific was only weeks away. By Owen Gault and Joseph Fanelli (Sea Classics, April 1996, volume 29, Number 4)

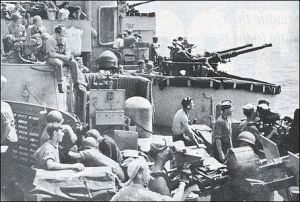

It was the kind of order Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 61 never expected so close to the brink of victory in the Pacific. Scuttlebutt on the lower decks had it that the nine-ship squadron had been handed a dangerous top-secret special assignment that would send them deep into Japanese territory never before penetrated by American surface ships. The strike mission would search the unknown waters for enemy shipping and would require complete radio silence regardless of the type of opposition the squadron encountered. The specter of this kind of action was what destroyermen lived and hoped for; were trained to do. But what the enlisted sailors didn't understand was the somber admonition that they were to scuttle their ships if attacked; that explosives had been placed aboard each ship to be detonated in all key communication areas so that American technology would not fall into the hands of the enemy should they be captured. To the 3000 men of DesRon 61 the rumored mission order was of deep concern. Was the US Navy now contemplating Japanese-style suicide missions, or was it the foolhardy quest of some glory-happy staff officer to make a name for himself? The strange order was mindful of the kind of do or die efforts so common in the early stages of the Pacific War when the Navy's desperate plight required desperate measures. But that era was now well behind them. The American fleet had fought its way from the disaster of Pearl Harbor to near total victory. Now, in mid-July 1945, Halsey's powerful 3rd Fleet was parading virtually unchallenged at Japan's doorstep. What was the point of mounting a mission that might have consequences serious enough to warrant scuttling many of the ships involved? Many asked if the scuttlebutt was true, yet none of ships' officers could deny that DesRon 61 had been given a special assignment with disturbing implications to every war weary crewman. For days now the American Fleet was bombarding the Japanese mainland around Honshu almost at will. Adding to the booming crescendos of the battleships SOUTH DAKOTA, INDIANA and MASSACHUSETTS' 16-inch guns were the relentless 8-inch staccatos of the heavy cruisers QUINCY and CHICAGO's main batteries, plus the massed five-inchers of nine fleet destroyers. Each booming salvo hammered to pulp what little remained of the military, industrial and rail head targets already smashed by the high-flying B-29s of the 20th Air Force. While there was much skepticism about the tactical value of the Navy's assault from the sea, no one in authority denied the bombardment was a blistering retribution for Japan's treachery in 1941. From the yardarm of each ship in the bombardment force flew two-blocked signal flags reminding all that the Navy would "Never forget Pearl Harbor." The powerful gunships of Task Force 38 offered a defiant challenge the Japanese were loathe to accept and powerless to stop. All movement ashore was at a standstill with most of Honshu's read, bridge and railway network already in shambles. Earlier, Admiral `Bull" Halsey had proclaimed that if Japan's populace was not pounded into submission his ships would starve them into submission. It was a promise the tenacious Halsey was determined to keep. Even the dreaded kamikazes had failed to appear in any significant number; the skies clear of anything except massed formations of Allied strike aircraft. What little was left afloat of Japan's once vaunted Imperial Navy was now bottled up in a naval siege that placed a final stranglehold on any hope of Japan's salvation from the sea. The all-out air and naval assault was but a prelude of what was to come next -the invasion of Japan's main home islands by Allied troops poised to launch what everyone believed would be the deadliest battle of World War II. Though Japan was on its knees staggering under the fury of Allied might, no one contested the prediction that the final victory would be costly. Should the Japanese fight to save their homeland with the same tenacious fury with which they defended Okinawa and Iwo Jima, it would be the war's worst bloodbath; the mother of all battles. Eighty miles off the Honshu coastline the nine destroyers of DesRon 61 continued to perform their assigned duties screening the fast carriers of Task Force 38. Under command of Vice Admiral John S. "Slew" McCain, flying his flag aboard the flagship carrier SHANGRI-LA, TF 38 had begun the final destruction of Japan from the sea. Assisting McCain was Rear Admiral Thomas Sprague, newly promoted from escort carriers, now commanding Task Group 38.1. As the squadron's nine near-new Sumner-class 2200-ton destroyers completed their refueling and drew maximum loads of ammunition and supplies, the ships' crews continued to debate the sinister meaning of the new orders handed down on 20 July. Annoying, too, was that even as they altered course to begin forming up for their perplexing new mission, they saw other reserve fleet escorts moving in to fill their assigned slots in the carrier screen. Many wondered why their slots were being filled so quickly; were they not expected to return? Of additional concern especially to the deck officers was the fact DesDiv 122 had no division commander of its own. With the division commander away on another assignment, Cmdr. William McClain would have to do double duty as both the destroyer TAUSSIG's skipper, and at the same time act as the division's leader, a troublesome dual workload under the best of circumstances. Another matter was the question of DesRon 61 possibly being fired at by other trigger-happy vessels, or the aircraft of TF 38 upon its return. There had been several recent instances of confusion and missed signals in the massive fleet operations in enemy home waters. It would be easy for the destroyers to be mistaken for a Japanese formation. Only weeks earlier an American submarine had been tragically sunk by carrier planes in a case of mistaken identity. One wrong code word in their IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) signals could bring every gun in the fleet and every plane in the sky down on them. Speculation and rumor ran rampant, but no reassurances came from the bridge or wardrooms. All that the destroyermen were told was that strict radio silence would be maintained and that demolition explosives would be on hand in all radar, fire control and communication bays in case the ships were badly damaged. No destroyer would be allowed to fall into enemy hands. Badly damaged, the ships were to be scuttled, sunk on the spot, the crews left to fend for themselves. In the ships' mess decks the troubled sailors freely debated if this was any way to end a war that to all appearances was so close to being won. Aboard the squadron's flagship USS DE HAVEN (DD-727) Captain T.H. Hederman paid little attention to the tribulations of the crew as he studied his orders. He had problems of his own with the new assignment. Hederman well knew that without a division commander for DesDiv 122, TAUSSIG's McClain was forced to act in a dual capacity. Should they come under intense fire, or meet unexpected opposition, anything might happen. In the heat of battle, directing the maneuvers of three fast-moving ships plus his own could lead to all manner of possible mayhem, confusion and collision. Masterminding the movement of his five ships in DesDiv 121 called for all the skill Hederman could muster. To have the added worry of four more "tin cans" without an experienced leader free of the chore of ship handling would require a vast change in his attack plan. Hederman would shepherd his flock accordingly -make them one big happy family - but at much higher risk than was necessary, or anticipated. The mission order was simple enough on paper. DesRon 61 was to make a daring anti-shipping strike deep in Sagami Nada (Gulf) on the night of 22-23 July. No other force of Allied surface ships had ever penetrated that deeply into the fringes of Japan's massive Tokyo Bay. If no shipping were encountered the destroyers were ordered to bombard shore installations as targets of opportunity. On the surface it was a seemingly straightforward assignment with no sinister implications. But the Japanese were known to be desperate to move men and equipment along the coastal waterways, the only avenues left to travel. This bred the chance of encountering Japanese warships that had been secreted for just such last-ditch missions. Likewise the location of shore batteries of unknown size and number posed another hazard. The real threat lay in drifting mines, or possible attack by explosive-laden suicide boats. Of these two dangers the presence of mines was the most probable. In the past week dozens had been found and destroyed as far as 80 miles off the coast by the ships of TF 38. Detected in broad daylight under a blistering July sun and sunk by the ship's 40mm guns, the mines had been easily spotted by sharp-eyed lookouts. Such was not the case in the assignment they had been handed. DesRon 61's mission would require steaming at high speed in the dead of night through uncharted waters no American surface ship had ever dared enter before. Hederman knew there was a serious element of risk in this, especially with the moon forecasted to be almost hidden by drifting layers of clouds. It was a risk he and the squadron would have to take. If nothing else, Hederman took solace that he knew he could count on his nine skippers to handle their ships well. Each ship and crew was already well battle-tested with most of the units having been in the thick of the Pacific raids, fighting for the better part of a year. Several had previously distinguished themselves in action and each had already earned at least one or two battle stars. The TAUSSIG had downed six enemy planes and was credited with aiding in the destruction of two others; LYMAN K. SWENSON had splashed two Japanese planes during the Okinawan campaign; MANSFIELD had knocked down a fighter only weeks earlier and the COLLETT had helped sink the Japanese submarine I-56 in April. Some, like the MADDOX had been damaged in the vicious duels against the kamikazes; and others, like the SAMUEL N. MOORS and the BLUE, had been damaged but survived the great typhoon that wracked the fleet in December 1944. If Hederman had any doubts about the mission that lay before him, they did not include concern that the ships of DesRon 61 could not be relied upon to give their all. Finally, the day had come. At 0600 on the morning of 21 July 1945, DesRon 61 detached itself from Task Group 38.1 with flagship DE HAVEN the first to depart as the formation guide. Following it in short order were the destroyers of DesDiv 121 -USS MANSFIELD (DD-728); LYMAN K. SWENSON (DD-729); COLLETT (DD-730) and MADDOX (DD-731). On their heels were the ships of DesDiv 122 with TAUSSIG (DD-746) leading the pact consisting of USS BLUE (DD-744); BRUSH (DD-745) and SAMUEL N. MOORS (DD-747). By late morning the ships had all replenished from the oilers and ammo ships, completed their radar calibrations and were now formed into a circular cruising disposition with DE HAVEN still in the lead. Happily, no radar contacts were reported and by late afternoon the squadron had formed into a single column to minimize the mine threat. As the four ships of DesDiv 122 now took up positions astern DesDiv 121 vaporous clouds gathered in the humid summer skies. Still in the lead, DE HAVEN began to encounter the last vestiges of a recent tropic typhoon; a heavy angry sea that caused Captain Hederman to order speed reduced to 15 knots. The morning of 22 July dragged slowly by with tension mounting as the formation drew ever closer to the unseen enemy coast. At 1223 MADDOX's radar came alive with the blips of six unidentified planes. General Quarters was sounded and the crew rushed to battle stations relieved at last that the nagging tedium had been broken. A tangible enemy they could see and cope with was far preferable than the endless worry of fear itself. Soon alert Bofors and Oerlikon guns swept the cloudy skies but the alert quickly proved to be a false alarm. The Bogies picked up 40 miles distant disappeared off the radar screens heading harmlessly to the northwest. At 1256 MADDOX secured from General Quarters and set conditions "II" and BAKER reduced states of readiness. An anxious calm returned to the ships, but only for a few precious hours. Still ahead lay foreboding Sagami Nada and the enigma of its unknown dangers. In mid-afternoon the DE HAVEN hoisted a signal on her halyards that she was leaving the column to scout the choppy waters in an attempt to determine the formation's maximum safe speed. By 1737 DE HAVEN returned and Captain Hederman now formed the ships in open order. Despite the sea conditions the formation would make its run at top speed, a tactical compromise between safety and their ability to accurately lay their guns on any sudden target. As the sun fell low on a hazy horizon the lookouts reported they thought they could see the silhouette of Nojima Saki peninsula far in the distance. Radar confirmed the distant land mass as the ships drew into the approaches to the broad expanse of Tokyo Bay. The formation passed checkpoint "Queen" on schedule and on course. All was going well and the nagging rumors slowly gave way to cautious optimism that the strike mission might yet prove to be a cake walk. Nightfall brought with it doubled lookouts who scanned the restless sea for any sign of floating mines. The familiar soothing hum of the blowers and throbbing engines helped to ease the crew's concerns. Soon a nervous calm settled over MADDOX and the other ships as half their men sought sleep in their cramped and stifling quarters. The eerie calm would not last long. With a nerve battering squeal, the ships' claxons suddenly sounded General Quarters at 2234. Drowsy sailors sprang from their bunks grabbing life jackets as they hurriedly ran to man battle stations on the pitching decks. Ready ammo lockers were opened and clips of 40mm Bofors and 20 mm Oerlikon ammunition were made readily at hand to feed the voracious breeches of these intermediate-range weapons. Fore and aft the heavily shielded twin 5-inch mounts grumbled into life as their motors whined at peak output ready to deal with any intruder. Thirty miles off the Japanese coast DE HAVEN's radar made a surface contact at 350 degrees at 29,600 yards - more than 16 miles away; course 100 degrees and speed of 15 knots. In seconds several of the other destroyers flashed signals that they also had contacts. At first the vague radar blips were thought to be land badly obscured in the reflective signal clutter of the heaving sea. If it were land the squadron was badly off course. Captain Hederman was convinced the squadron was on course; that the jagged radar blips were enemy ships and not a spur of land. At 2315 the contact became clearly identified on the scopes - four ships heading on an easterly course at nine knots; type, size and armament unknown. MADDOX quickly changed course left to 300 degrees at Captain Hederman's order to go to 27 knots. Signal lamps now busily flapped orders through the murky darkness as DesDiv 122 took up their assigned positions 3000 yards astern of DesDiv 121; also increasing their speed to 27 knots. Now the positioning orders came fast and furious as blinkers of light flashed constant changes to each ship. At 2339 MADDOX swung hard left to a heading of 060 degrees true. Minutes later she angled to the right to 090 degrees, then at 2345 turned her bow farther to the right to 120 degrees; then left again to 090 at 2347. Each turn was calculated to give the squadron its best intercept angle against the Japanese ships. Totally unknown was the enemy vessels' size and intent. From their speed Hederman gambled they were merchantmen of about three to five thousand tons; that the smallest in the vanguard was most likely an escorting gunboat or mine sweeper. With all guns and torpedoes manned, engines at all-out speed and adrenaline wildly pumping through every crewman's veins, the DE HAVEN and the MADDOX charged headlong toward their unseen foe with all seven sisters in close pursuit. To McClain on the bridge of the TAUSSIG, the mass maneuver in the dim moonlight seemed tantamount to the naval version of a classic cavalry charge. Far to the horizon, he thought he saw gun flashes erupting from the shoreline, but no shells fell near them. Excitement and danger filled the air as the nine ships swung their radar directed guns into the blackness of the night waiting for the order to open fire. The MADDOX's official Action Report gives the best and typical account of what happened next: 2350 Prepared to fire a partial salvo of two torpedoes to port. Selected large target of two ships in close formation bearing 048 degrees, 13,350 yards. 2351 Target bearing 038 at 13,300 yards, speed 9 knots. Fired two torpedoes to port. 2353 Opened rapid fire with main (5-inch) battery on largest target, bearing 032, 13,000 yards. 2357 Checked fire. Turned right to course 130. 2358 Resumed rapid fire, bearing 014, target 12,900 yards. 2359 Changed speed to 30 knots. The ship's clock struck midnight as the feverishly working gunners in each of MADDOX's three twin 5-inch mounts cleared their smoking gun tubes: 0000 Checked fire. Shifted target to (enemy) ship which was firing random shots skyward. This (enemy) ship was not yet on fire. Turned left to 090 degrees. Speed 30 knots. 0002 Resumed fire. Gun flashes spotted from shoreline. 0003 Turned left to 060. 0004 Checked fire. 0005 Resumed fire, bearing 340 degrees, 14,300 yards. 0008 Ceased firing. Expended 398 rounds 5"/38 cal. AA common projectiles and 398 rounds flashless powder. 0009 Changed course right to 140 degrees and began high-speed retirement. 1729 Rejoined Task Force 38. In the dead of night DesRon 61 had intercepted a four-ship convoy sneaking along the coast of Sagami Nada en route to Tokyo harbor. Rushing to attack, several of the destroyers launched torpedoes almost simultaneously and, like MADDOX, quickly opened a heavy volley of main battery fire that soon had the lead ship afire and fast sinking by the bow. In rapid order the two other accompanying ships burst into flame and when last seen were close to sinking. The fourth ship in the convoy was thought to be a small naval escort which turned away out of the line of fire, possibly damaged by the destroyers' opening salvos. While the destroyers first reacted as though the large leading enemy ship was firing at them, it was later agreed that in the blackness of the night the hapless Japanese vessels thought they were under air attack. Also, the bursts of return shellfire from enemy shore batteries fell too far away from the darting destroyers to be of any serious consequence. Obviously confused, the Japanese gunners had made a vain attempt to scare off the phantom Allied planes with their AA guns blindly firing into the night sky. Because of the range and lack of visibility it could not be determined if the ships succumbed to either the avalanche of unleashed torpedoes, or to the horrendous cascade of 5-inch shells raining upon them. Several large successive explosions were seen to erupt from each of the ships followed by fires that lit the brooding night sky for miles. No, credit for the sinkings could be given to any one single destroyer that engaged in the attack. In less than 15 breathless minutes the last surface shootout of the Pacific War had begun and ended. No mines or other enemy vessels were encountered in this swift moving anti-shipping strike at the gates of Honshu. Despite the fears that beset so many the mission came off with near flawless precision - a fast hit-and-run strike deep in enemy waters that sunk at least one large cargo ship, probably sank and positively badly damaged three other medium-sized freighters and their naval escort. Crewmen's fears that upon their return they might accidentally be fired upon by their own ships or aircraft also proved unfounded. By late on the afternoon of 23 July each destroyer was safely back in its assigned slot with Task Force 38.1. Learning the success of DesRon 61's mission, Admiral Halsey in his endorsement of Captain Hederman's report on the action noted that division commanders should not be detached from command of tactical units without proper relief, as in the case of DesDiv 122. Yet despite the added burden of dual commands placed on him, Cmdr. McClain of the TAUSSIG had proved to be an exceptionally resourceful skipper who managed both tasks well. The next day the Navy struck at Kure, Japan's largest naval base. What little remained of Japan's navy soon lay in smoldering ruin as the 105 United States warships and 28 British naval vessels of Halsey's 3rd fleet pounded enemy shore targets almost with impunity. Two weeks later the atomic bombs that fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki rang down the final curtain on the war against Japan. On 2 September 1945 Japan surrendered unconditionally to the Allies. The Allied Fleet had come to stay in Tokyo Bay. Although the events of the night of 22/23 July in Sagami Gulf would be quickly forgotten in the jubilation of victory that followed, they would be long remembered by the men of DesRon 61. No satisfactory explanation for the strange scuttling orders was ever given, and some insist that demolition explosives were never placed aboard any of the nine ships in question. In the Navy's understandable paranoia that followed the licking taken by its destroyers at the hands of Okinawa's kamikaze, the idea of scuttling a damaged ship in the heart of enemy waters possibly made sense. What is more difficult to comprehend is that little official mention of the destroyers' night action in Tokyo Bay was ever made public. Nor were the ships' crews commended for their daring in steaming so boldly into harm's way. For a time it was rumored that President Harry Truman contemplated requesting a medal be struck and awarded in their honor, but no verification of this suggestion was ever made. Though little remembered today, the events on that dark night so long ago will never be forgotten by the veterans of DesRon 61. To a man they take humble comfort that they performed well and proudly in the last surface battle of World War II. Editor's Note: The author wishes to express his appreciation for the help and data provided by former crewman Joseph Fanelli of Dayton, Ohio, who served aboard the USS MADDOX during the strike in Tokyo Bay.

|