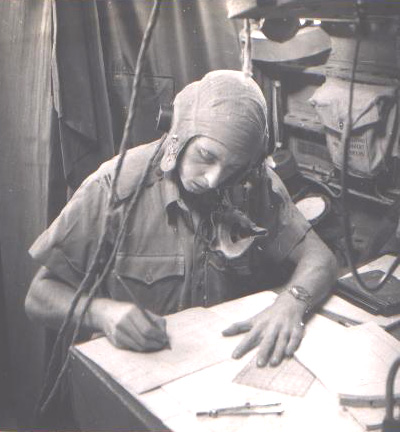

‘MAYDAY’ in the Tsushima Strait – December 1953by Derek Empson Group Captain RAF (Retired) In December 1953, I was a UK Royal Air Force Flying Officer, the navigator and captain of a Sunderland long-range maritime patrol flying boat of No. 88 Squadron. Each squadron crew had its own aircraft and mine was RN302. The Short Sunderland first entered squadron service in 1938 and was one of the RAF’s principle long range aircraft engaged in defending trans-Atlantic convoys from the United States to Great Britain during the Battle of the Atlantic in World War II. RAF Coastal Command Sunderlands were credited with sinking twenty-seven German U-boats. The particular Mark of Sunderland we were operating during the Korean War was the Mark 5, powered by four Pratt and Whitney Twin Wasp R1830-90B engines, the same as fitted to the Douglas DC-3 Dakota. Our particular crew had three officers, one warrant officer and six SNCOs. There were two pilots, two flight engineers, three air signalers, two air gunners and me, the navigator. Three other RAF Sunderlands were on detachment at Iwakuni airbase, near Hiroshima, Japan, at any one time. We shared the base with two USN VP squadrons, one flying PB4Y Privateers and the other, PBM-5 Mariners, the latter like the Sunderland, being flying boats.

Throughout the Korean War and the armistice period after July 1953, both USN and RAF aircraft and crews shared the task of flying anti-shipping surveillance patrols daily over the Sea of Japan, the Tsushima Strait and throughout the Yellow Sea area to the north of Shanghai. A patrol lasted anything from nine to twelve-and-a-half hours depending on the patrol area and the number of shipping contacts we detected, reconnoitered, photographed and reported. Patrols were also flown every night in the Yellow Sea to collect cloud, weather, wind, temperature and barometric pressure data at various pre-planned locations. We passed these data, usually at about 3am, by VHF to a Task Unit of Task Force 77 or 95 for use by their naval and air forces for the coming day’s operations. Most weather systems moved towards Korea from Communist China and the Chinese were not then disseminating Met information. We less often flew night patrols in the Sea of Japan. When flown, these extended northwards to within a hundred miles of Vladivostok. I believe these patrols were ordered to be flown by Iwakuni-based aircraft only when aircraft carriers of TF77 were being refueled and re-supplied at sea (RAS) off the northeast coast of Korea when fixed-wing aircraft would be unable to operate freely from the carriers. Our crew in Sunderland RN302 (C - Charlie) had set off from Iwakuni on Christmas Eve, 24th December 1953, to complete a Fox Blue shipping surveillance mission in the Yellow Sea west of Korea. An hour and a half later, while transiting over the Tsushima Strait en route to the patrol area, there was an explosion (a few feet from my left ear), followed by flames emitting from the starboard inner engine The extinguishers put out the fire, we shut down the engine, feathered the propeller and I gave the pilot the Course for Iwakuni. We returned to base, without difficulty or further incident, landing on three engines 3 hours 10 minutes after we had taken off at 6.45am. Having flown on Christmas Eve we were off duty on Christmas Day, but on Boxing Day 26th December, our crew went to Base Operations to be briefed by the duty USN operations officer for an Anti Shipping Patrol in the Tsushima Strait the following day. Our RAF maintenance engineers said they would have our aircraft, RN302 ‘Charlie’, ready to fly by the morning having rectified the cause of the engine failure on 24th. The next day, 27th December, we got out of bed at 4.45am and took off from Iwakuni as briefed at 06:15 hrs. We transited to the Shimonoseki Strait patrol area at low altitude below the cloud base. We began our patrol, flying at about 1,200 feet. Flight Lieutenant Jack Oliver was then in the left-hand (1st pilot’s) seat and Flying Officer Sandy Innes-Smith in the co-pilot’s seat. At 08:25 hrs, we were well into our patrol and were heading north just to the east of Tsushima Island. I happened to be standing with my head in the astrodome, looking east along and beyond our starboard wing when suddenly our No. 4 engine (the starboard outer) emitted a flash accompanied by an explosion followed by flames and black smoke which streamed back over the wing as I watched. The pilots immediately shut down the engine, feathered the propeller and activated the fire extinguisher. After a couple of minutes, outward indications were that the fire had been put out. Flames could no longer be seen outside the engine cowling. Flight Lieutenant Jack Oliver set the other three engines to maximum climbing power, as stated in Pilot’s Notes, but he soon complained that he was finding it impossible to maintain height. It was at about this time that one of the flight engineers reported from the lower deck that No. 2 engine, the port inner, was losing oil and beginning to emit some smoke. Quite possibly, therefore, this engine was not delivering the expected power and may have been why the pilots were finding it impossible to maintain height. As we would probably have used no more than 350 to 450 gallons of fuel since we took off, we would have been above our maximum recommended landing weight. There was a short discussion as to whether to jettison fuel. I think we decided against this for two reasons: the possible fire risk and because there was too little time to jettison enough fuel to make a worthwhile difference to the aircraft’s weight and hence to arrest its rate of descent. Our altitude was by now probably between 750 and 1,000 feet. The 1st pilot said he felt we would have to land very soon because we were continually losing height. I felt that if we were going to have to land, we needed to set the aircraft up properly for a landing and not be forced into it in a semi-prepared state. Although I was the aircraft captain, Jack was a very experienced pilot and I felt in no position to doubt his judgment as to the necessity to land at such short notice. The Pilot’s Notes stated that a heavy aircraft should be able to maintain height on three engines if set to maximum climbing power and the dead engine is feathered (which ours was); indeed, we had successfully returned to base on three engines only three days ago as well as on two further occasions in December alone. Although reasonably reliable for the 1950s (an average of one engine failure per 1,000 flight hours) the Pratt and Whitney R1830 engines were getting old, and that month in Japan, for some reason we had been suffering a spate of engine failures, many more than usual – including on this particular aircraft; it was our second failure on RN302. Having already shut down No. 4 engine and since there were indications that all was not well with No. 2, it was probable that the total power available was not sufficient to maintain height at our aircraft’s present weight. We transmitted a MAYDAY message on 121.5 Mhz, stating our emergency and our intention to land (or ditch) the aircraft on the sea. We were then heading north, parallel to the east coast of Tsushima Island which was a mile or less to port. I think we were flying roughly into wind. The pilots sounded ‘L’ (dit-dah-dit-dit), for ‘Landing’, on the aircraft’s warning horn and pre-landing checks were quickly completed by the crew who then took up crash landing positions. I removed the astrodome (which provides a crew escape exit); the flight engineer stowed the dome securely behind the instrument panel in his compartment. I then took up my own crash position. The surface wind was probably no more than 10-12 knots but there was an appreciable, long swell. These were not good conditions for landing. The combination of a relatively low wind speed and our high weight meant that our speed over the sea at touch-down would probably be around 80 knots. The pilot would have to try to prevent the aircraft’s bow from burying itself into one of the rising swell crests as the aircraft slowed after touch-down, especially if or when we were thrown into the air again by a swell crest. We were now flying on three engines and about to land on a northerly heading approximately in position 34° 37’N 129° 30’E. I was sitting on the upper deck floor, facing aft behind the main spar and had no view of the actual touch down. As far as I can remember, we were thrown off the water at least three times. The second impact was especially violent but my impression was that the aircraft had remained in a slightly nose up attitude throughout, thus avoiding the danger of burying its nose into the sea. We seemed to stop in a remarkably short time. I jumped onto the platform beneath the astrodome escape hatch and looked out. My immediate concern was whether either of the wing floats had been ripped off in which case the crew would quickly have to carry out ‘broken float drill’ – that meant sitting on the wing on which the float was undamaged, to prevent the other wing from entering the sea and possibly making the aircraft turn turtle. Both floats were intact. However, looking to port I was astonished to see that the No. 1 (port outer) engine had broken free from its mountings during one of the aircraft’s impacts with the sea and had disappeared; only a dangling trail of cables and pipes remained. I then looked aft and saw that apart from a small section of the leading edge, the remainder of the starboard horizontal tail plane was also missing. It, too, had fallen into the sea, presumably swept away by a combination of the vertical impact and being struck by the sea surface. There were no injuries to the crew and a quick inspection showed that, thankfully, the main hull was sound and without leaks.

Looking to our left (west), less than half a mile away was a coastal inlet about 400 to 500 yards in length and at most 250 yards wide. The pilots maneuvered the aircraft slowly into this coastal inlet using the remaining serviceable port and starboard inner engines both of which were still running. Normally, aircraft were taxied using the outer engines because they provide more leverage for turning without building up too much speed; the aircraft had no sea rudder. The inlet into which we taxied had rocky sides and soundings indicated that the water was deep. With some difficulty we eventually managed to stop and anchor the aircraft near the far end of the inlet. We shut down both engines and started the auxiliary power unit to provide electrical power. We sent a message by HF W/T to Iwakuni, up-dating them on our situation and location. On further inspecting the aircraft it became evident that the main spar supporting the wings had fractured during the landing; RN302 (C) was clearly a Category 5 ‘write off’. I told the crew to gather all documents, especially everything that was classified or sensitive, and to begin dismantling as many instrument and electronic modules, radio sets, the IFF, etc. as we could, for future use as spare parts at Iwakuni. We didn’t know at this stage how we would recover them there but knew they would be useful.

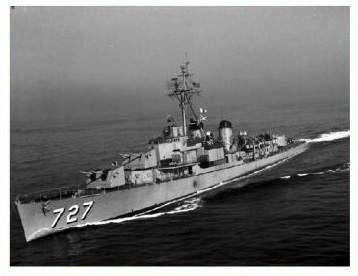

Within an hour of landing, a USAF search and rescue (SAR) Albatross amphibian, believed to have been from the 3rd Air Rescue Squadron based at Ashiya, circled overhead, then landed on the sea close to the entrance into the inlet where we were anchored and taxied towards us. We spoke to the SAR Albatross crew and established what should best be done. I considered we no longer needed a full crew and several were therefore put aboard the Albatross. This aircraft then took-off, using rocket assisted take-off (RATO) to get airborne in an incredibly short distance, possibly even within the inlet in which we had anchored. Later that day, we were pleased to see the Destroyer, USS De Haven, DD-727, appear about a mile off shore and drop anchor. An officer from the ship, whom I now believe was the 1st Lieutenant, Hal Smith, came with others by motor launch to see what assistance we needed and to discuss future action. It was agreed we would later be taken aboard the USS De Haven and one of the ship’s launches would the next day tow RN302 to sea and, assuming permission was given, the De Haven would sink RN302 by gunfire in deep water to remove it as a hazard. Another member of the crew of USS De Haven on board the launch when our crew was later taken to the Destroyer was Eric Brummitt, a Hospital Corpsman, with whom I have also recently be in email contact.

The next day, 28th December, our aircraft was duly towed out to sea to a position roughly a mile off shore and about 250 to 300 yards from the De Haven. This can be seen in the photographs, two of which were taken by another RAF Sunderland that was fortuitously circling overhead. Our crew’s last sight of RN302 was when a single 3 inch shell from the USS De Haven hit the aircraft amidships. There was a split-second pause, and then a ‘woof!’ and a flash as RN302 exploded, soon disappearing beneath the waves below a pall of black smoke. The result can be seen in the photograph. The remainder of our crew, all now aboard the USS De Haven, had been made welcome by the captain and crew, and had been found accommodation. I and another member of our crew to whom I spoke recently, remember that the standard of food served aboard was excellent. We spent the next three days at sea, more or less having the run of the ship but trying not to get into anybody’s way. We were used to locating and identifying ships from a few hundreds of feet, but this was a rare opportunity to see a warship and its very professional crew at work - and to compare its equipment with ours. The USS De Haven rejoined the task force that included the CVA USS Boxer (CV-21) and a number of destroyers and frigates. One of these was a Royal New Zealand Navy, Loch Class Frigate. Before the Korean Armistice period, RNZN frigate crews had apparently several times made night landings against coastal targets in Korea and taken prisoners for intelligence gathering purposes. The USN CVA Boxer also had a distinguished record completing four cruises during the Korean War and the post Armistice period. The USS De Haven (DD-727) on which we were now embarked, also had a proud naval record winning no fewer than six battle stars during the Korean War. After three days at sea we docked at the US Naval base at Sasebo on Kyushu. There, we said a grateful farewell to our rescuers and friends in the USS De Haven. We disembarked together with the equipment we had removed from RN302. We were then taken by road to Itazuki airbase from whence Lt Cdr Jose USN, flew us to Iwakuni on 1st January 1954 in a USN R5D transport aircraft (Registration No. 50875). Although our stay aboard the De Haven had followed from an unwelcome event - which nevertheless could have had far worse consequences – it was a heartening and encouraging experience of comradeship between different military services and Allied nations. I was interested to read recently that, twenty years after this event, in December 1973, the USS De Haven was transferred to the Republic of Korea and re-named Inchon.

As is standard practice, an RAF Court of Inquiry was set up on our return to Iwakuni, to gather evidence on the circumstances of the loss of RN302 on 27th December. The two pilots, other crew members and I as the aircraft captain and navigator gave our evidence. After the enquiry had been completed, on 16th January we took-off from Iwakuni in Sunderland PP137 (O-Oboe), as passengers – we now had no aircraft of our own - bound for Hong Kong. We were flying with Flight Lieutenant Peter Wildy and his crew; but as if it somehow knew that we were on board, and to prove a point, No. 2 engine almost immediately began to give trouble. The pilot shut it down and we returned to Iwakuni on three engines! We finally departed Iwakuni on 18th January and returned to our base in Singapore after a two-month absence. Before my tour in the Far East was over I twice again returned to Iwakuni for Korean operations. This was in February/March and again from June to August 1954, completing another twenty-seven Korean patrols that brought my total to sixty-one. The RAF then ceased operations from Japan.

My experience of flying in the Korean theater was never dull and was at times very challenging. It had also been a period during which I had the privilege and pleasure of working closely with the US Navy who controlled our day-to-day operations. This was an experience I was to repeat almost thirty years later when I was Chief of Staff under Rear Admiral Bodensteiner USN, Commander Maritime Air Forces Mediterranean in Naples, Italy. The help we received from the De Haven in December 1953, and the few days we spent on board, stand out as some of my most memorable recollections of that period. I wish all former sailors of the De Haven, God Speed, and offer a special ‘thank you’ to those who happened to be present off Tsushima Island on 27th December 1953 when Sunderland RN302 came to grief. I hope this account of what happened on that occasion will be of some interest to those former US Naval personnel who were serving on board USS De Haven (DD-727) at that time, some of whom I’m delighted to say, have been kind enough to contact me.

The seaplane as photographed by Dale Harbin The explosion of the three-inch shell photographed by Dale Harbin

Derek Empson Group Captain RAF (Retired) Knutsford, Cheshire, England The author's book about this incident will be available March, 2010

|